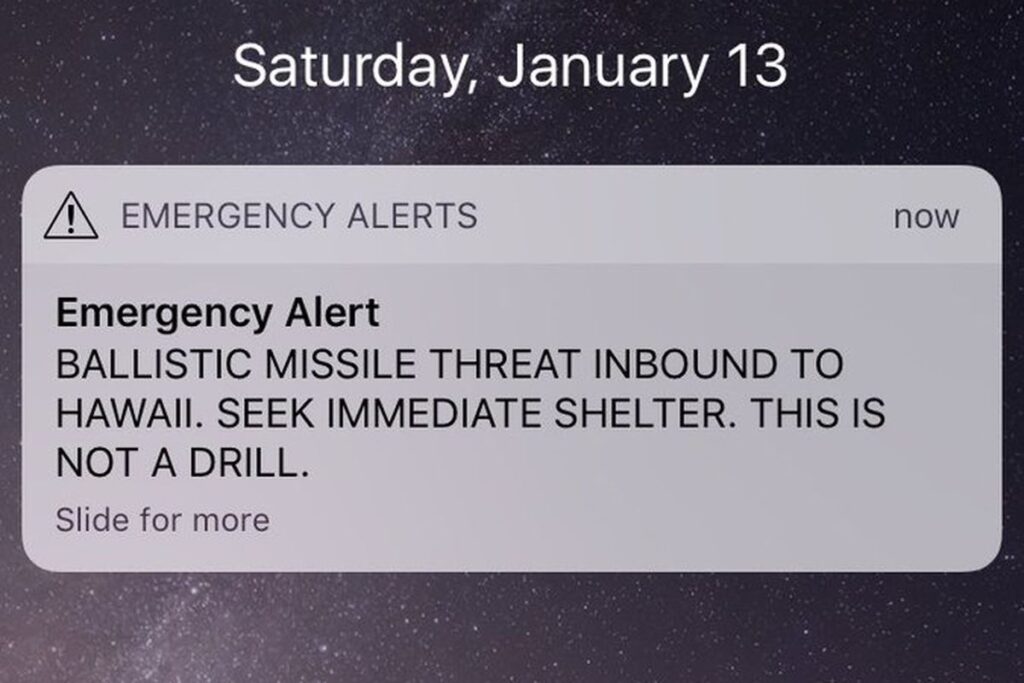

Hawaii False Ballistic Missile Alert

At 8:07 am local time, residents and guests of the Hawaiian Islands received a concerning alert broadcast on television, radio, and cellphones. The alert read, “Emergency Alert: BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.” Immediate panic broke out across the islands and on social media with residents unsure of how to react or what to do. No outdoor warning sirens were sounded. For 38 minutes following this critical alert, there was radio silence from the Hawaiian Emergency Management Agency or state officials. Residents said their last goodbyes to their loved ones and flooded the 911 telephone system searching for what to do. At 8:45am, the emergency system eventually sent a second alert relaying a false alarm. This alert read, “There is no missile threat or danger to the State of Hawaii. Repeat. False Alarm.” Investigations by state officials later revealed that the false alarm was due to the failure of a single employee, but the true issue was discovered to be the system itself being flawed for a technical communication of that importance.

One important function of technical communication is of governments or groups alerting the general public to arising dangers that they may face. Longer term dangers may be addressed by technical communications such as publications and reports from agencies such as the CDC or the White House, but there is also a need for short term danger communication. As expected, this short-term communication is extremely powerful because of the widespread coverage on nearly all electronic devices and important messages that it carries. These emergency alerts in particular are extremely powerful because of how essential they can be and how citizens will follow the direction in these messages without a second thought. This means that the content and rhetoric of these messages is of critical importance and every word choice needs to be precise and accurate. This requirement was one of the reasons that only prerecorded and prearranged messages were able the be sent by the Hawaiian message system, costing nearly 40 minutes to reprogram a follow up message clarifying the error. One can imagine the problems associated with having a “blank message” of sort that can be filled with any text and sent out immediately, but sometimes radio silence in the case of an emergency is not acceptable. In a world where hackers threaten nearly every electronic system, the security associated with a flexible message system like that would need to be impenetrable.

From this case study, there are some clear messages about the future of emergency alerts and instantaneous technical communications to citizens. The instant nature of the internet and smart phones offer a unique situation to educate people on important events or dangers to the second rather than just a few hundred years ago where you may have to wait a few days to read about it in the paper. The failures of the Hawaiian system raise important questions about the President Alert text system that was set up in October of 2019 to send a message to every cellphone in the country. Amber alert and flash flood warning messages have been used successfully for years due to their simple blueprint and consistent content. A system with the power to message every phone in the United States must have the peak level of technical communication with every content and rhetoric choice being infallible. When you have every citizen listening and responding to these messages as if their lives may be on the line, every letter is critical.

The video below provides more background and shows instances of the emotional turmoil caused by the false alert.

Resources

- Hawaii Crisis Communication Case Study: What We Can Learn from the Hawaii Missile False Alarm, blog.pocketstop.com/hawaii-crisis-communication-case-study-can-learn-hawaii-missile-false-alarm-14185.

- Shepherd, Christena. “Government Quality Management Systems: Case Study from the Hawaii Missile Alert.” Asq.org.

Recent Comments