Columbia Space Shuttle Disaster and PowerPoint

Just before 9 a.m. on February 1, 2003 the space shuttle Columbia was poised to return to Earth after 16 days in orbit. As the shuttle was beginning its usual landing approach to Kennedy Space Center, an abnormal loss of sensor readings alerted Mission Control that something was amiss. The Columbia was travelling at 18 times the speed of sound and located about 4 miles above the Earth’s surface when communications were lost. Mission control was left in silence waiting for final approach from the Columbia while news networks across the US were broadcasting video of the shuttle breaking up in the sky. There were no survivors among the 7 astronauts onboard. Weeks of forensic research determined the cause of the crash was impact from a piece of foam on takeoff damaging the wing of the shuttle. Deeper research showed that despite the years of engineering and planning, the downfall could be attributed to a technical communication failure following the debris damage and prior to reentry. In simple terms, years of engineering work from the smartest minds the world has to offer were undone by a few PowerPoint slides.

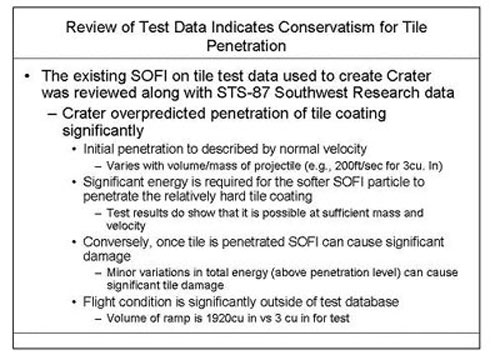

Internal technical communication can be critical for engineering collaborations and companies. It can be difficult for highly specific and technical information to be communicated effectively while maintaining a degree of accuracy as well as maintaining the sheer amount of information. This was evident with three PowerPoint reports prepared by Boeing Corporation engineers assessing possible damage to the left wing by foam 81 seconds after liftoff. These three reports conveyed an over-optimistic evaluation of the data to the NASA officials that were tasked with making the decisions for the flight of the Columbia. In order to simplify the large amount of data to a few PPT slides, the engineers had to choose which information was important enough to include and had to make more general statements about data which was not important enough to include. One example is of an “Executive Summary” slide where the bold face title was “Test Data Indicates Conservatism for Tile Penetration”, conveying a positive result of the test data.

The data itself, however, was nowhere near as reassuring as the title suggested. Smaller bullets on the slide indicate that the actual flight condition was significantly outside of the test database and the actual debris that struck the Columbia was estimated to be 640 times larger than the data used for the test model. It is not inherently incorrect to only use models at hand and make decisions from those, but the rhetoric and content choice of the technical communication points readers to a different truth than the data is telling. Further vague rhetoric and inconsistencies in the slides impeded understanding by the executives and portrayed the debris damage issue incorrectly. It is important to note that it was not necessarily the data and the tests that were inherently incorrect, it was the translation and technical communication to the decision makers where the truth was “lost in translation”.

This case shows us the importance of content and rhetoric when using technical communication in a detail and data-oriented field. Not only is the content important, but something as simple as the bullet hierarchy in a PowerPoint slide can have devastating impacts. It is important when communicating to be sure that you are not only accurately conveying data, but also not misleading the reader to an imprecise conclusion.

Resources:

- Howell, Elizabeth. “Columbia Disaster: What Happened, What NASA Learned.” Space.com, Space, 1 Feb. 2019, www.space.com/19436-columbia-disaster.html.

- Tufte, Edward R. The Cognitive Style of PowerPoint. Graphics Press, 2003.

Recent Comments